Podiatric Surgery – a Fairy Tale Come True

Part 5: The History of Podiatry in the Making

Podiatric surgery was a fairy tale that came true. The profession of chiropody moved to podiatry in a manner which went from the impossible to to the attainable. This article skates along the story and pathway that has yet not be told but existed. Read Part 2 here.

‘Deceive one’s self; for what a man wishes he generally believes to be true.’ Demosthenes (384-322BC).

Podiatry was a profession that would have been unlikely to go beyond the superficial structures of the foot. Quite simply it did not have medical acceptability or if I was honest the technical ability. The lack of foundation medicine, absence of access to medication to reverse the effects of surgical complications, without access to diagnostics, even the basic practice of utilising x-rays was outside our reach in the sixties. Even in the seventies with the advent of local anaesthetics we were ill equipped and yet we prevailed. Forty-seven years later we are at the pinnacle of a major change. 2024 should be the big date to celebrate half a century of development.

This article has been Peer Reviewed 2021

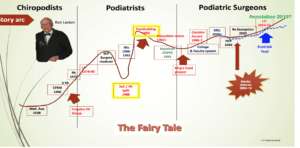

The Fairy Tale Graph shows founder Ron Laxton and The Croydon Post-graduate Group. see larger picture using link below https://consultingfootpain.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fairytalegraph.docx

Did we deceive ourselves?

Were we correct in the early days to take on the surgical establishment armed only with local anaesthetic and no other drugs? All prescription drugs were provided legally by GPs. As Alexander Pope put it, ‘fools rush in where Angels fear to tread’, based on ‘why agree to conduct a symphony when you’ve never heard it!’ Chiropodists of that time were still trying to move away from chemical disinfection of their instruments before the Little Sister autoclave, although developed by 1966, was introduced slowly to podiatry in 1980.

Was it a case of two biblical characters clashing?

We could consider putting David slaying Goliath on the front of the cover but then this would have almost certainly be misunderstood as a misrepresentation of who the enemy or predators were. Was the enemy orthopaedics? Or, was it a regulator as existed before 2003? For one it was natural protectionism, the other just the usual time needed to establish a new health opportunity. The regulator, the Council for Professions Supplementary to Medicine was ill equipped to deal with surgery within its’ family. Despite the fact that orthopaedics was better established through the Hunterian structure of the Royal College of Surgeons, and underpinned by medical training. They were better educated, had larger in numbers. Constituted as part of the medical fraternity of thousands and established more than a century earlier. They had the right, the license and legal support to be pre-eminent in the field of foot surgery. However, the podiatrist (sic) knew from experience that in many cases the giant was not that good and tinkered with foot surgery. In 1991, Leslie Klenerman, a well respected orthopaedic surgeon, and interested in feet wrote,

‘The development of podiatry may have come about because of a lack of orthopaedic interest in foot surgery, driving patients to seek alternative sources of help’.

Mr Klenerman accepted that poor interest in the foot would need to change and so a specialist orthopaedic Group now called BoFAS emerged. The British Orthopaedic Association developed their interest group called BOFSS or the British Orthopaedic Foot Surgery Society. The Government of the day had no difficulty with competition if it did not cost anything to the exchequer. Human consent was loose enough to allow us to work within our competency. In fact this was where we started. Nail surgery and some skin lesions, mainly verrucae. To the horror of an outsider, all podiatrists developed their skills slowly and grew the specialty. It was not a case of diving in and undertaking bunion or flat foot surgery as we do today. Politicians and journalists showed little interest in podiatry during the seventies and litigation had not reached the scale it has back in the seventies. Efforts to discredit correspondence courses by our own profession backfired when debated on the 1980’s BBC Watchdog programme Nationwide. Such courses had greater political support and did little real harm and were tolerated.

The Dawning of evidence for surgery

Practising outside the NHS we lacked evidence that we could contribute to healthcare. It was not until Dr Clare Laxton[i], an independent researcher, published a cross professional paper in 1985 that we had our first impartial view of podiatric surgery. Nail surgery really looked good in the hands of podiatrists and poor in the hands of surgeons but equivocal when it came to digital lesser toe surgery. Surgical tutors started to push their trainees to write referenced papers, go back and take top up degrees usually at Bachelor level. Today the key journals THE PODIATRIST and JFAR have displaced Podiatry Now. Although it is too early to make a judgement, The Podiatrist could well play a different role compared to Podiatry Now and the previous in-house journal, British Journal of Podiatry, that sought scientific gravitas. The Foot, a lightweight academic journal was displaced for the Journal of Foot and Ankle Researchand considered a journal of choice because it had a high impact factor. This score relates to citation trends per annum. The advantage JFAR has over The Foot is its’ development into an open access resource and therefore more accessible than in-house journals. The researcher or institution pays the fee for publishing. Positive editorials were published in the General Practitioner (1995)[ii] and Foot and Ankle Surgery (2002)[iii], and articles such as Helm & Ravi (2003) raised greater awareness of the rapid progress that podiatric surgery was making. Podiatric surgeons had by now brought a wide range of publications into view largely resting on audit of centres demonstrating activity.

Collecting hard data

More evidence had to be gathered to establish the capacity of our role in the NHS. PASCOM–2000[iv] was established to collect large data over the next 28 years. At the time of writing, the database has reached over 99,500 patients. The system morphed into PASCOM-10 in 2010 as a web based resource centre for members of the College of Podiatry.

Politics and the Golden Gate

Politicians were more interested in healthcare deficits being filled where the risk was low and remained cost neutral. But it was not until Margaret Thatcher and her State Secretary for Health Kenneth Clarke battled with the medical establishment following a review which led to the paper Working for Patients in 1989 that change took hold. The control the medical profession had was eroded as the BMA found they could not take on the Thatcher Government and win. This went on to allow a free market approach to healthcare. This was the golden gate podiatric surgeons had been waiting for. With growing development within the NHS podiatric surgery was attractive to GPs who were interested in day case surgery and lower cost delivery. Orthopaedic waiting lists had become exponentially longer in the NHS and private practice was lucrative as patients sought out private consultations. During the early nineties three significant life changing factors occurred for podiatric surgery. First the British Orthopaedic Association rejected the Commission on the Provision of Surgical Services report (CoPSS). Secondly this threw a disparate Podiatry Association back into the formal organisation having split from the Society of Chiropodists in 1988. Thirdly, and of more momentous impact was our formal competition with orthopaedics through GP Fundholding. We had started to optimise our profession and work within the NHS network, but this was not going to make us friends with orthopaedics anytime soon.

King’s Fund Project

After 1993 podiatric surgery gained new acceptance within the framework of an NHS service due to changes in the GP budget holding community. This was based around patient choice – a euphemism for most cost effective. A number of publications supported our activity and also the quality of delivery, but the gravitas behind our research methodology was still in its infancy. A King’s Fund project gave legitimacy to the growing evidence which arose through a spin-off from a 1994 executive report of the NHS Executive chiropody task force, Feet First[v]. Podiatric surgery was identified as one area of interest. The publication[vi] became the blueprint for our future at a time when the College of Podiatry emerged from collaborative talks in 1996. This became a major game saver for the Podiatry Association brought down by costly expenses during the lean years when it tried to go it alone with a dwindling membership. A smooth career road had yet to emerge for podiatric surgery into the nations’ largest employer – the NHS. The King’s Fund publication provided evidence and explanation at an academic and political level that there was a place for podiatric surgery in national healthcare. Podiatric surgery still needed better definition. The advent of an undergraduate, and thereafter post-graduate MSc programme led to improved research and quality publications and was a positive outcome from the task force project. A MSc based entry into podiatric surgery was established and this exists today and will soon be enhanced by ‘Annotation’ supported by Health Education England, endorsed by the HCPC and the College of Podiatry.

A storm brews

Orthopaedic surgeons saw podiatric surgery as a threat and used methods to expose natural weaknesses in the podiatric surgeon’s defence wall. Interestingly they missed out on the difficulties podiatric surgeons faced with prescribing key drugs but access to prescription drugs came with exemptions in 1997 within the 1968 Medicines Act, then with independent prescribing after 2012. Many podiatric surgeons functioned effectively with local patient group protocols during the years when drug access was limited. No patients were left uncovered and all activity legitimately accessed by independent pharmaceutical scrutiny.

An attack was made through a report by Matthew Freudman in 2004 using a survey. Reported in The Times.[vii] The publication raised concerns of a threat to its trainee surgeons (BOTA) and the fact that the public thought podiatric surgeons were medical doctors. While the article was disputed as being ‘no danger to the public’ by the organisation’s Dean of the Faculty of Podiatric Surgery at the time, many criticised the quality of the survey which appeared flawed by leading questions. Additionally, it was clear medics as exemplified by anaesthetists were not considered medically qualified. By 2008 Devlin for The Telegraph told a similar story calling for banning of the title surgeon. Anna Cavell for the BBC London reported problems of podiatric surgeons misleading the public in 2009. This form of communication used imagery and patient interviews to dramatic effect. Banner lines such as lack of accreditation for podiatric surgery were cited. The implications that no-one was overseeing the training of podiatric surgeons.

‘BBC London has learned that there is no independent body which accredits these training courses.’

Despite being briefed by the SCP Publicity department and two other Deans, on 2nd July 2012 Louis Rogers for The Daily Mail misled the public as to the length of podiatric surgical training. But, she was right, there was no independent body accrediting training. Subterfuge mixed with half -truths had been used to find the soft belly of podiatric surgery. The Health Care Professions Council replaced the old Council of the Professions Supplementary to Medicine in 2003. Prior ‘weak’ annotation existing under the qualification ‘FPodA’ used by the Podiatry Associations’ qualified podiatrists with the former Council was removed on the new register. Annotation was intended to help the public identify who practised surgery and thus distinguish them from the role of general podiatry. The HCPC believed their statute restricted them to podiatry alone and interpretation should be applied equally to the speciality of podiatric surgery. Cavell’s report had put the HCPC on the defensive, but what she had done was stirred up a hornet’s nest. Although unpopular and damning the report did little harm outside the College, but it transformed internal attitudes as successive Deans and faculty members debated how to manage growing concerns. The outcomes, painful as they were at the time were positive.

Improving publicity

As with all publicity, negative and positive, fall out can itself be helpful. The profession reflected on the black hole that might appear in terms of understanding of who we were. Two key leaflets were produced and later a U-tube based film. All podiatric surgeons reviewed their approach to patient interviews. At a BOA-BoFAS committee meeting the Dean gained positive recognition for his Faculty development of patient advisory leaflets covering title and expectations[viii]. By now the profession had established websites and information was made clearer to support oral emphasis that podiatrists practising surgery were not medical doctors (or orthopaedic surgeons). There were strong feelings that dentists did not have to admit they were not medically qualified; so why should podiatrists equally able to perform invasive surgery? The HCPC found that they were under pressure and six podiatric surgeons found cases raised against them. Not one case led to sanctions or upheld unfitness to practise but much suspicion lay with someone actively counselling patients to complain. The distinction between the length and depth of training, and responsibility in surgical practise, could be described as a ‘Grand Canyon’ gap. Podiatry 3 years and podiatric surgery 11-12 years. Communication had failed all round and the Faculty at the time had to accept some responsibility, even though that the main flaw was with other agencies. The HCPC cited their legal statute and limitations of imposing new changes within the Allied Health Professions register. The College tried to reach a common goal and unblock any obstruction to progress. The waves produced by the media slowly settled as all parties started new talks which appear to have held.

Professional Development Continues

Podiatry has made much progress over five decades with a stronger evidence base than it started with. There are better research ethics fostered by higher degree education. Podiatric surgeons are better trained than ever before, but their requirements typically have pushed them into more years of study and clinical exposure making this a costly career to follow, often without guaranteed job prospects. It may appear almost coincidental but a publication of a document covering manpower as far as those AHP professions are concerned showed that recruitment to podiatry had negative growth. Coincidentally orthopaedic foot and ankle surgery and podiatric surgery share the same dilemma. Poor workforce planning and funding. Competition has not ceased neither will there be peace until national manpower is addressed. The risk from all this white noise inevitably reduces the quality care offered to patients by both professions in the United Kingdom.

![]()

[i] Laxton, C Clinical Audit of Forefoot Surgery performed by Registered Medical Practitioners and Podiatrists. J. Public Health Medicine 1995.17:311-317

[ii] Editorial. ‘GPs Praise Podiatry’. General Practitioner. 24 Feb. 1995

[iii] Editorial. ‘Chiropody, podiatry and orthopaedics.’ Foot and Ankle Surgery 2002;8(2):83

[iv] Rudge G, Tollafield D.R. A Critical Assessment of a New Evaluation for Podiatric Surgical Outcome Analysis 2003;6(4):109-119

[v] HMSO Feet First. London: NHS Executive 1995;1-28

[vi] Carter, J, Farrell, C, Torgerson, D The Cost-effectiveness of podiatric surgery services. Kings Fund. 1997

[vii] Hawkes, N Consultant foot doctors’ tread on orthopaedic surgeons’ toes. 2004, August:6. This relates to Freudmann’s article for B.O.T.A

[viii] Faculty of Podiatric Surgery together with all other Faculties (medicine, management and education) changed to Directorate of Podiatric Surgery in 2014.

Thanks for reading a ‘Podiatric surgery – a Fairy Tale’ come True by David R Tollafield as part of History of Podiatry in the Making

Recent Comments