An introduction to surgery for podiatrists and non-foot surgeons

Incisional surgery for Morton’s neuroma is widely used, especially after conservative care has failed. Surgery either forms an approach using minimal portal incision or open surgery. Unfortunately even in competent hands neuroma surgery varies between 50-85% success (Di Caprio 2018)

Principle approaches

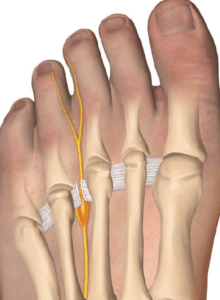

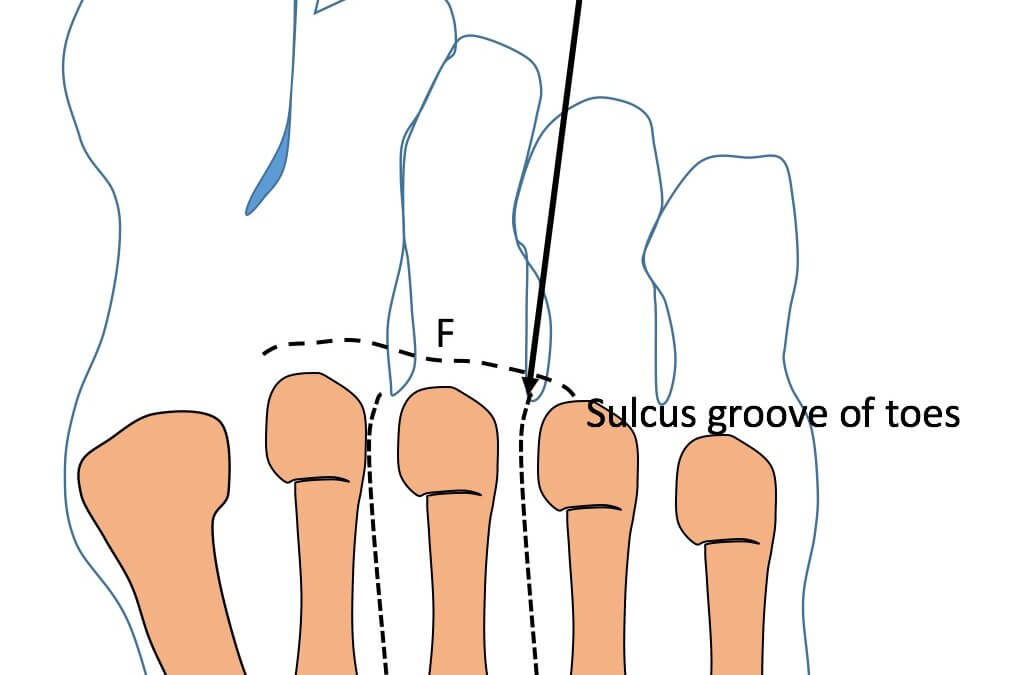

There are four principle approaches that have been described to gain access to plantar digital neuroma (PDN). Hoadley (1893) entered the intermetatarsal space from the sole, while McElvenny (1943) split the webspace. Nissen (1948) used a transverse cut on the sole instead of the longitudinal access of Hoadley, and McKeever (1952) accessed the space from the dorsum.

With the advent of endoscopy and smaller probe designs, some surgeons have attempted to make smaller incisions. However, without a doubt, the main approaches practised are the plantar incision and dorsal incision.

Surgical techniques can be found in the usual podiatric and orthopaedic textbooks dedicated to foot surgery. For the sake of clarity, this article will focus on plantar and dorsal incisions and the quality of evidence.

Quality research papers are often criticised for their lack of controls, the introduction of bias with confounding factors, and poor comparison methods to assess outcomes. It is for this reason that there are limited citations in this summary of incisional surgery. For the most part, the relevance of the content will predominantly interest foot surgeons, but patients will ask questions about surgery. For this reason, I wrote a book covering my own experience – Morton’s Neuroma. Podiatrist Turned patient: my journey.

decompressing the nerve is a popular MIS technique but the success depends on the size and pathology of the neuroma.

Literature review

Di Caprio (2018) and Valisena (2017) have provided literature and a systematic review respectively. Generally, the meta-analysis is more powerful, making use of like for like comparisons. Both reports consider conservative (stage 1) treatment, and Valisena looks at the second stage with infiltrative (injectable) treatment. The designs tend to dilute the depth of analysis as the subject matter is cast widely. Di Caprio admits in conclusion that a quality analysis was not performed nor a comparison of results in terms of assessment tools, e.g. AOFAS, VAS.

Di Caprio points to the plantar incision offering better visibility without the need to incise the deep metatarsal transverse ligament (DMTL). The plantar transverse incision (Nissen 1948) is placed near the fold to avoid scarring on the load-bearing surface. An endoscopic release can be used without macroscopic changes to the nerve (Villas, 2008). Di Caprio reports overall surgery successes reported from 51-85% for long term studies. Patients did better with single space neuromata than multiple spaced sites. There was no difference between spaces 2 and 3 for beneficial outcomes. Complications ranged from delayed wound healing, hypertrophic scar formation and inclusion cyst. Numbness post-surgery varied. Recurrence of neuromata also varied from 14-21%, and the causes were listed:

- Wrong diagnosis

- Failure to divide the DMTL

- Resection was too distal for the plantar digital nerve

- An association with tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) was not recognised

- Incomplete removal

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is one condition that all specialists should consider being not as uncommon as one might believe. Additionally, treatment of both can be challenging and this author believes it is better to try conservative care and isolate surgery to the PDN initially rather than attempt tibial nerve release.

Meta-analysis

Valisena (2018) considered retrospective, prospective and random controlled studies for 17 surgical reports. The analysis uses a detailed series of spreadsheet tables to provide an overview of surgical and non-surgical treatment covering method and design and results from satisfaction, follow-up, failures, complications and statistical analysis. The authors of this review considered most articles from the case series, many of which were excluded for poor design or failure to note criteria for inclusion/exclusion and mixed conditions associated with metatarsalgia.

Surgical reports ran from 1994 – 2013, of which 11/17 (65%) papers were retrospective, 4/17 (24%) papers were prospective and 2/17 (11%) were RCT. Twenty-five approaches were listed. Dorsal and plantar incisional approaches were easy to find, but ‘open’ or ‘resection’ offered little value. There was a mixture of some DMTL releases, of which only 2 suggested directly that these were minimal incisional surgery (MIS). Thirteen cases were performed dorsally and 4 cases plantarly. Follow-ups ranged from 1 to 240 months with a mean of 6 – 180 months. Participant numbers varied widely from 17-145. Overall satisfaction for all surgeries 65-100% (mean 89%) with failures from 3.8 – 36%. (4%) and complications 25%. Unlike Di Caprio, Valisena identified complex regional pain syndrome among the usual complications and dysfunctional stiffness and floating toes. One presumes the latter arose where metatarsals and joints were included in the surgery.

Incisional surgery should be the last choice

One of the inescapable aspects of managing neuroma is the fact that there is no single treatment. If not introduced early and with good patient compliance, conservative care will lead to exponential failure or, at best, injection treatment will become less valuable if repeated over time. We have learned that factors influence success, of which some have yet to be investigated within a random controlled study (RCT).

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Age

- Gender

- Size of neuroma

- Symptom duration

- Medical co-morbidities

- The webspace involved

- Anatomical variation (Govsa 2007)

- Presence of other forefoot pathology

- (e.g Hallux valgus, lesser toe deformities)

-

-

-

-

-

For the most part, it is the size of the neuroma that makes a difference, the presence of forefoot pathology, symptom duration and extent of nerve pathology, Tollafield 2021. Herein lies the problem. Unless the nerve is removed, no histology can routinely be used to determine the extent of neural damage at the cellular level. If surgery is to be avoided, then the above factors should be considered as early as possible.

The impact of surgical problems

Tollafield (2017) considered complications in surgical risk and impact from neurectomies rather than frequency alone. Data was collected from the Royal College of Podiatry database PASCOM-10 for 2016. The basis of risk should not be the only factor that surgery must consider because the impact factor can have a range of consequences on the quality of life. In a database caseload review of 944 patients, 74.1% had no complications with Level 3 complications, affecting 11.7% of patients. Level 4 was affected by 2.9%, which implies a notable impact on life and post-operative recovery.

- Expected frequently with surgery. Features are short-lived and do not involve surgery or significant interventions

- Expected but less frequently.May remain over 3-12 months and then disappear slowly

- Not expected – but could happen; borderline sequella, but complications may arise. It may have consequences. Longer treatment times and possible surgery may be required

- Not expected, low chance of occurring– always known as a Consequences for function and mobility, some permanent loss possible. Loss of part, surgery required. Usually containable. Usually requires further surgery

- Difficult to predict, very low likelihood of arising– serious Direct effect on life, possible death, hospitalisation with attendant secondary problems.

Neurectomy incisions

Habashy (2016) and Akermark (2013) provide some insight into the difference between dorsal and plantar incisions. Habashy used the Short Form Health Survey SF-36 and Foot Function Index (FFI), while Akermark used the VAS score. Habashy looked at neurectomy outcomes in patients between the two incisory locations, while Akermark used a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) for the same. Out of the two, only Akermark was cited in Thomson’s systematic review. The question remains the same; is there a benefit in undertaking surgery in one incisory location?

In both cases, the second and third interspaces formed the key locations for neurectomies. Habashy ended with only 37 patients for 42 neuromata responding to survey questionnaires out of the original 161identified patients, resulting in 20 patients with 21 dorsal neurectomies and 17 patients with 21 plantar neurectomies. Akermark had 76 patients out of 97 patients with 76 neuromata. Again, non-surgical management was used, including orthoses and injections. Thirty-one (31) neuromata were performed through the dorsal aspect and 25 through the plantar aspect.

Habashy did not provide a record of complications, and overall some of the outcome data were poor except for tables on SF-36 and FFI scores. They concluded that both dorsal and plantar approaches produced satisfactory outcomes. Akermark was far more informative and identified some interesting data on complications. Sensory deprivation causing some patient concerns were identified in 66% of cases of plantar incision and 85% of cases for the dorsal incision. There were 5 complications in the plantar group and 6 in the dorsal group. The scar in the post-operative healing review with a mean 34 month follow up suggested no plantar scar or only mild concerns problems in 90% of cases and dorsal cases in 96%. Akermark used a different surgeon for each type of incision and follow up was not blinded. An independent observer implemented a validated questionnaire. No significant differences were shown in either study and Akermark’s conclusion, results were equally good 87% plantar and 83% dorsal. They noted dorsal approaches were technically more difficult. Dorsal incisions can lead to missed nerves and accidental removal of blood vessels. Additionally, they were aware of the rare but real concerns of CRPS.

Additional information on surgical approaches

The web splitting technique offered by McElvenny is still selected either as an open or minimal incisional approach. Masaragian (2020) used VAS and AOFAS scales over 49 months for 83 patients. Complications in 3.5% included persistent pain over the scar zone and superficial wound infections. The study was retrospective and formed a case series. Arauz (2020) provided a second study which interestingly was from a different location in Argentina. The interdigital approach performed in 108 patients was again retrospective and called ‘commissural’. VAS was used alone. Histology confirmed all neuromata were accurately diagnosed. At 8 year follow up the subjective sensory loss with discomfort arose in 12.9% of cases with overall satisfaction of 74.2%. The rating of satisfaction has no reference. Despite having reasonable follow-up and case numbers, both papers would be rejected by a systematic review and were considered level 4 case series.

Conclusion

Given the wide range of approaches, all forms of access have some success. Numbness remains a common problem but troubles people differently. The risk of a stump neuroma can amplify pain, making the initial surgery disappointing. Surgery should not be attempted until both conservative care and injection therapy have been used together with an appropriate imaging analysis to identify the size and differentiate other pathology, especially a bursa. As a general rule, an 85% overall success rate might be prudent when surgery is considered.

See other articles covering Morton’s neuroma (plantar digital neuroma) on this site; 1-6. Originally published for clinicians. Dates in brackets

Available from AMAZON books in ebook and paperback format

- Is back history valuable or just padding. [26th November 2021]

- Morton’s Neuroma. Old Problem, New Analysis. [6th Dec. 2021]

- The Unsung and discredited management of Morton’s neuroma. Pathways and approaches. [9th Dec. 2021]

- Injection, neurolysis and sclerosis. [14th Dec. 2021]

- Thermal or surgical choices for Morton’s Neuroma. [16th Dec. 2021]

- Incisional surgery for Morton’s neuroma [18th December 2021]

![]()

For references to these and other related articles, I have produced a list of past and current material valuable for research and clinical discussion click REFERENCE HERE.

Thank you for reading ‘Incisional Surgery for Morton’s Neuroma’ by David R Tollafield

Have you read all six articles on Morton’s neuroma? Read the first in the series Metatarsalgia & the Foot Neuroma

Sign-up for here my regular FREE newsfeed

Published by Busypencilcase Communications. Est. 2015 for ConsultingFootPain

Recent Comments