Oiling the Cogs of his career

A Career Series in podiatry – Martin Fox

What is the vascular podiatrist? As with dermatology, sports podiatry and forensics, sub-specialisation opens the door to both career progression and offering the healthcare system people who develop skills that can integrate with medicine. Martin Fox is no exception but the cogs of his career came from people who believed in him and by him adopting a can-do attitude, overcoming lack of confidence, which in his case was no obstacle. Here is his tale.

Martin was a classic school leaver and qualified as a podiatrist in 1990. He entered podiatry college aged 18 after ‘A’ Levels and while he had good ‘O’ Levels, he says he messed up his ’A’ Levels. Having conducted several interviews with podiatrists this is not so uncommon in men. Buckling down to study during your late teens it is easy to become distracted. Knowing this was his experience it is important to remind all students that while we might mess up, it is not the end of the world. Martin provides clear evidence as he has risen to the top of his profession having selected podiatry. The question on my lips was what drove him into podiatry?

“I needed to open up my options, but at the same time I’d been thinking about healthcare, and I’d looked at ideas like veterinary science. I’d looked at physiotherapy, nursing even toyed with the idea of becoming a male midwife. I’m not quite sure why! But in hindsight, I’ve married a midwife, so maybe I’ve got in that way. I didn’t really know about podiatry, but I liked the idea of a clinical specialism in the health of the human body. I think if anything, the reality of the fact that I could walk into what was at that point, a three-year Diploma in one of many cities around the UK made me think – I’ll try this.”

The unknown opportunity

Within three months of not being sure what he was doing, he moved to Salford from a small village in Yorkshire. Today of course podiatry has a degree course and entry into the field requires A levels or equivalent. Podiatry is relatively easier to find a place compared to physiotherapy and medicine, but this is because of low competition and lack of awareness of the option as an exciting and challenging healthcare career. One of the reasons that few knew about podiatry when at school was the fact that careers officers had no real idea of the scope and breadth of this profession. To some extent this still exists, and it is often by default, through personal experience or word of mouth that students find podiatry and realise that there are many exciting options.

Martin landed a job after a delay, having volunteered for the National Trust, building dry stone walls in the Lake District. At the time podiatric surgery, diabetes work and biomechanics were defining an early route to specialism. Martin points out that there wasn’t a natural career path into the management of the high-risk lower limb.

Early days and influence

Martin spent five years in general podiatry which provided experience working with the elderly, basic wound care, nail surgery, care of the superficial structures such as the skin and nail problem management. As with Podiatrists Ben Yates and Alison Clarke-Morris, and still in his twenties, he wanted to travel and expand his horizons and contributions to healthcare. He wrote to a non-governmental organisation in Kolkata (Calcutta at the time), working with street people, run by a British doctor in partnership with Indian local workers. To request a sort of sabbatical. We see again that some managers are willing to release people to gain wider experience.

“I went to India with a rucksac, suitcase full of sharp implements and a few donations of dressings and things and ended up in Calcutta one morning working in a tent by the river. To be there one Monday morning, having never travelled out of Europe, was amazing really, having come from working in a very standard NHS community clinic. It was suddenly like the lightbulb went on, and I thought, this is quite amazing that I’ve taken myself here, as a podiatrist.”

With a short term offer to come for a few months to volunteer clinically, Martin went into the leprosy clinic. He observed complex wound care, physiotherapy and medicines alongside social care. He likened it to a multidisciplinary team (MDT) clinic without walls. The clinic was an open tent with a doctor, some nurses and healthcare assistants and a physiotherapist. This inspired Martin to view the lower limb as part of his expertise and skill set and set up a sustainable project that resulted in a permanent footwear and insole workshop. This provided protective ‘offloading’ sandals for homeless people with leprosy. Arriving home after a year, armed with his profound experience with a leprosy unit, he promoted the opportunity for others, recruiting and sending out more podiatrists in the following years.

Recognising the importance of the at-risk limb

Thinking outside the box

The route to a career in managing the high-risk limb was undefined at the time Martin was pioneering changes in the perception and scope of practice for podiatry. Commencing with a clinic in a tent and disadvantaged people on another continent, he took his essential podiatry skills and insights to a new level in the community around Manchester.

“I could contribute to an area of healthcare that we hadn’t been working in before. I was proud to be a podiatrist and valued the skill set that I had because without us being there, the nurses and the doctors and physios had been trying to do the bits that we do well with the lower limb, but really not have the focus, knowledge depth and the putting things together that we can do.”

Back in the UK his quest led him to a role within diabetes, a growing field of specialty for podiatrists. Influenced by podiatrists who had led the field beforehand and inspired by their leadership and vision. Martin was offered a community diabetes podiatry job in Tameside, East Manchester. He applied his field experience to the community.

“It was the first job of its kind really because previously this role had been hospital-based rather than conducted in the community, something I now valued from working in Calcutta. The idea of working closer to where patients lived, connected the clinic with their environment and could offer better access and sometimes better outcomes than in existing hospital settings.”

Supplied with a room, a laptop and mobile phone he designed the community diabetes podiatry job from scratch. Inspiration expanded with the support of his progressive manager and working with a friendly vascular surgeon. Prior to this the podiatry experience with surgeons had not been successful. Many consultant surgeons would not even speak to podiatrists or accept direct referrals, such was the ignorance about the specialty and value that could be offered. For the first time the vascular surgeon saw Martin as somebody who didn’t carry out basic care and could be trusted with a high-risk foot. Some thought podiatrists might cause harm, so patients ended up with the vascular surgeons giving them more work! It is important to realise just how far podiatry has travelled in opening the landscape of choice and opportunity. Any sense of animosity and cooperation has now disappeared in the 21st century and diabetes and podiatry are not just linked at the level of hospital care but politically; recognised as saving limbs and preserving lives. The importance of podiatry is often mentioned during Parliamentary debate in a positive light.

Martin shadowed the surgeon helped by a forward-thinking nurse in tissue viability – the name given to caring for the lower limb deteriorating through a poor blood supply.

“This nurse helped oil the cogs of my career, to get into the vascular side of podiatry because she introduced me to the surgeon informally. My own boss (a podiatrist) allowed me to pilot a Friday morning session on the vascular clinics where the tissue viability nurses, also a vascular specialist nurses and the vascular surgeons looked at the lower limbs together. We came up with a plan for each patient about the next steps, involving podiatry, nursing and surgical perspectives.”

Following on from Martin’s scalpel skills, his knowledge of pulses, and extensive knowledge of wound care, he expanded into vascular clinical diagnostics. Using handheld Doppler equipment, he undertook measurement of blood flow categorising measurements with flow through the arm and leg expressed as a value called the Ankle-brachial index. This value provides some predictability of how good circulation is through the limb to the foot.

Following on from Martin’s scalpel skills, his knowledge of pulses, and extensive knowledge of wound care, he expanded into vascular clinical diagnostics. Using handheld Doppler equipment, he undertook measurement of blood flow categorising measurements with flow through the arm and leg expressed as a value called the Ankle-brachial index. This value provides some predictability of how good circulation is through the limb to the foot.

Removing a diseased part of the foot without full surgical anaesthesia might seem strange, but because diabetes often had no nerve sensation, neuropathic diabetic and leprotic patients felt no pain. Alongside the vascular consultants and registrars, who usually performed complex out-patient wound debridement, Martin took on shared responsibility and fuller use of his podiatry knowledge and skills to identify blood vessel disease and turn around the patient’s deterioration and amputation risks positively.

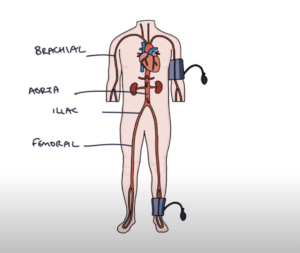

With confidence he expanded his knowledge and skills taking on more complex wound care, encroaching the leg and cardiovascular risk needs, rather than just foot health. As the podiatric surgeon takes on a wider assessment of medical health, the musculoskeletal podiatrist examines the upper body and pelvis, Martin had to evaluate pulses behind the knees, into the groin and even in the tummy. This made sense as the blood supply does not start in the foot – it ends there. (see figure aorta and iliac vessels)

“I learned how to feel for an aneurysm on the tummy. The surgeon was saying, if you’re seeing these patients, Martin, and they’re not coming to me anymore because they’re seeing you and you’re turning them around to be managed by the GPs for their leg and cardiovascular risks, perhaps you can learn to examine the tummy & palpate the abdominal aorta… so that if there is an undiagnosed aneurysm sitting under that belly, you too can sometimes find it and make sure those patients do come to us.”

When he found his first large aortic aneurysm it was a moment not to be forgotten. If he had missed this vital clue the patient could have died. “The work really is about lives and limbs,” he chants. Podiatrists have certainly had to extend their ability and skills because not doing so fails common sense and value of what this professional is providing for the health care system. Before long femoral pulse auscultation (listening with a stethoscope or doppler) led to him being persuaded that if he was to become a vascular practitioner, with a focus on the lower limb, he needed to be doing the other things as well. He asked the consultant,

“Well, how much more do I need to know and do?” – it was a case of where do we stop? “I needed to work within the sphere of lower limb health but branch out and start feeling pulses elsewhere in the body, thinking and acting holistically and reporting things like irregular pulses back to the GP for diagnosis of possible atrial fibrillation. As well as determining the presence and severity of lower limb arterial disease, triaging people for GP-led cardiovascular management and exercise treatment or to the vascular team for limb revascularisation and amputation prevention. This way of working, using much more of my podiatry degree knowledge, started to become more normal, giving great job satisfaction.”

The Vascular practitioner develops

Martin believes that as clinicians we should lead on lower limb healthcare as we reduce the boundaries with other professionals that have historically ‘owned’ the knee, hip, vascular disease, wound care or dermatology. As podiatry branches out and realises its full potential, he feels we should accept shared responsibility where relevant, elsewhere in the body. Vascular podiatry is an exciting new specialty, overlapping with the diabetic and high-risk foot, providing early diagnosis and best treatment for life and limb-threatening circulation disease, working in collaboration with hospital vascular teams, set in accessible community clinics. Supporting healthcare provision became even more important during the COVID pandemic, when access to hospital services needed to focus on urgent life and limb-threatening needs. Being knowledgeable in the vascular system is essential and knowing the venous and arterial tree well.

Martin believes that as clinicians we should lead on lower limb healthcare as we reduce the boundaries with other professionals that have historically ‘owned’ the knee, hip, vascular disease, wound care or dermatology. As podiatry branches out and realises its full potential, he feels we should accept shared responsibility where relevant, elsewhere in the body. Vascular podiatry is an exciting new specialty, overlapping with the diabetic and high-risk foot, providing early diagnosis and best treatment for life and limb-threatening circulation disease, working in collaboration with hospital vascular teams, set in accessible community clinics. Supporting healthcare provision became even more important during the COVID pandemic, when access to hospital services needed to focus on urgent life and limb-threatening needs. Being knowledgeable in the vascular system is essential and knowing the venous and arterial tree well.

Taking capillary pressures is now a standard part of the undergraduate assessment in feet. Sarah Walsh. Student Podiatrist University Salford with permission.

Taking a good clinical history is vital together with social history. We cover limb oedema (swelling) and changes in the skin with the effects of poor supply. The ultrasound Doppler and blood pressure tests in arms, ankles and toes are vital to match clinical findings with factual changes in pulse quality, pressures and the types of waves. All this information can make a prediction as to the risk associated with vascular disease from amputations to aneurysms to clots and thickening of the walls of blood vessels. The most recent development is auscultation to identify irregular heart rhythms which may not otherwise be picked up in general medical practice. The vascular podiatry specialist can detect when the peripheral arterial disease is life or limb-threatening and ensure that people understand their diagnosis and signpost them into lifelong effective treatments:

- Ensuring people are prescribed the best cardiovascular medicines

- Implementing and opening up access to exercise treatment programmes

- Improving the efficiency of referral and early diagnosis of arterial disease

- Reducing unnecessary referrals to Vascular Surgeons by around 80%

Career awareness

A school leaver often finds podiatry as an alternative to their preferred option but once discovered can seek out new opportunities. There is no such thing as failure, only adjustment and reflection driving a new educational pathway leading to a fulfilling career in the healthcare market.

The experience that Martin Fox presents shows that over the course of his career he has thrown himself into new ideas and pushed the boundaries of podiatry, to better meet the population’s health needs for improved diagnosis and treatment of lower limb arterial disease. This has led to writing journal articles and book chapters, presenting at local, national and international conferences and even presenting on Vascular Podiatry to All Party Parliamentary committees in the Houses of Parliament. Not bad for a young man who once messed up his A levels. One can practice at different levels but if you really want to specialise in protecting limbs and saving lives, the climate and population need is ever present to make a new contribution with podiatry.

More information on the Ankle-brachial index assessment from Physio-pedia. Accessed 24/2/22

Podiatry as a career choice? An overview of podiatry for the school leaver

Sign-up for here my regular FREE newsfeed

Thanks for reading ‘The Vascular Podiatrist’ by David R Tollafield and Martin Fox was taken from an interview based on the Landscape project

Published by Busypencilcase Communications. Est. 2015 for ConsultingFootPain

Recent Comments