Plantar digital neuroma

Concepts of cause and pathology

A digital neuroma has been described since the 19th century and may appear as a well-established entity, new analysis comes along all the time. Splicing disparate information together is important and this article teases out some of the theories that contribute to this foot metatarsalgia. The source of papers come from orthopaedic, radiology, neurology and podiatry. Overall there are some 1200 papers available written in English but it is unknown how many have been published in other languages.

You can read the No.1 first article here.

Keywords – PDN plantar digital neuroma. MTPJ metatarsophalangeal joint

A picture emerges that the plantar digital neuroma is a nerve entrapment associated with chronic trauma, often provoked by footwear. Morton, a name often associated with PDN did not really know what he was dealing with and his surgery was crude. Civinini in 1835 understood this as a soft lesion and Durlacher (1845) recognised the neuralgic side of the condition. In contrast, Morton thought it was predominantly joint-related.

The true extent of pathology can only be determined by histology, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging methods. Clinical methods of identifying the condition are reliable for thumb-finger pressure and Mulder’s click. The click is pathognomic for the nerve as the nerve size increases, resisted by the transverse intermetatarsal ligament where a bursa is more flexible.

Characteristically the measurable size is more likely to be greater than 5mm to show dramatic signs but paraesthesia can arise earlier without the two clinical signs being evident. Neuritis changes nerve conduction sensitivity and may well be the cause of bizarre shooting sensations (Satkevicuite, 2018). axon transportation is disturbed when the inflammatory agents increase nociceptor sensitivity and signals are promoted centrally rather the just locally.

As the lesion increases in size, symptoms may escalate and can even breakthrough sleep, albeit less commonly reported. Bencardino (2000) found that on a retrospective MRI review of 85 patient images that 19 had positive MRI findings without symptoms after correlating with patients by questionnaire. Sizes varied from 2-9mm for the asymptomatic group. While there is no definitive explanation the two potential reasons for an increase in size without symptoms might come down to the lesion remaining flexible enough to avoid irritation.

Differential diagnosis

Common differential diagnosis includes synovitis of the MTPJ, avascular necrosis (Freiberg’s infraction), bursitis, gout, bone bruising to the metatarsal head, and stress fracture (March #) as well as true neoplasia. The presence of sensory changes can arise from other causes including nutritional, chemical and drugs, although more general.

Radiating pain toward the ankle and even the knee is not so uncommon. We have to add on Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome as a potential referred pain which can in rare cases be co-associated with plantar digital neuroma. The cause of a neuroma are formed in part from theories, observations, and tissue examination at surgery and under the microscope.

Renaut’s bodies

From the earliest reports, footwear and injury are the main causes of nerve damage and this damage if unabated will lead to changes in the bundles around nerves lined by the perineurium, epineurium or the endoneurium. The resultant effect is scar tissue and so fibrosis of any of these linings is reported on histology as well as an increase in size. Scar tissue reduces elasticity and the natural ability to move with other anatomical structures, especially around the centre metatarsals will provoke symptoms.

DeHeer (2020) drew attention to the spidery fibroblasts called Renaut bodies which are found near sites of nerve compression. Autopsy and tissue studies show the presence of Renaut bodies in peripheral nerves associated with thickened sub perineurial capillaries. They are not present in all nerves but the association with mechanical factors are important in the pathogenesis of nerve alterations which further suggests they do not protect nerve fibres from mechanical stress.

In an autopsy study of the pathology of chronic subclinical nerve entrapment, Renaut bodies showed a strong predilection for sites of nerve entrapment. They were present at these sites in 43 of 74 peripheral nerves but in none of the control sections of the same nerves. While mechanical factors are important in the pathogenesis of Renaut bodies there is no evidence to support the theory that these structures protect nerve fibres from mechanical stress Jefferson (1981).

Ischaemic influence

Blood vessels run through nerve fascicles and they show end arterial thickening as well as vascular proliferation as can be seen in gross samples taken from live subjects during surgery. There is also the presence of oedema in the endoneurium. One is drawn to ask why we need to know the detail. The relevance of pathology will emerge as an important part of understanding how to plan treatment and assess the best approach. Unfortunately, all the main systematic (meta-analysis) reviews do not draw treatment and pathology together, and treatments often emerge with little scientific critique except reporting on the basis of percentage success.

New treatments based on injection are in fact reviewed on the basis of reversing some of the fibroblastic activity. We need to turn our attention to the principle causes that create neural fibroblastic degeneration that leads to axonal degeneration. To date, no study has shown any outcome based on vascular changes to the nerve but injections aimed at neurolysis or sclerosing with ethanol in rat sciatic nerves undertaken by Mazoch (2014) and cited by DeHeer (2021) might suggest some changes arise. Data is far too small to draw any meaningful conclusion.

Topp (2006) presents an important series of facts regarding the compression of nerves. While nerves can cope with tensile and shear forces unless damaged, compression, when elevated above 30mmHg for over 2 hours, creates oedema and beyond 8 hours can create ischaemia. Given that feet are housed in tight shoes and compression arises collaterally from narrow shoes, it does not take a rocket scientist to realise that some feet are more prone to this problem.

What causes fibrosis?

Most clinicians understand the pathology of tissue healing and damage together with axonal degeneration but in the case of the PDN, there have to be inciting factors. Infection has never been suggested so it remains mechanical in nature. The Mulder test creates both pain and a pop sound as the neuroma rides over the adjacent ligament lying above the nerve. It is for this reason that many surgeons prefer a plantar approach so as not to disturb this structure.

Equally, there are minimalists who cut the ligament alone to relieve the pressure on the nerve and hopefully reverse the changes that are slow and progressive. As a sufferer myself and having had surgery after conservative care, the length of time from inception to resolution can take >1 year to 7 years or more. Morton reported a case that had tolerated the pain for 30 years.

Too little, too late?

There is no standard baseline for symptoms as reported by Bencardino (2000). The most commonly assumed reason for compression comes from shoes and the group who suffer most are females by a factor of anything from 3-10 times. In my own case, I used a tight cycle shoe that clipped into my bike pedal and nerve damage escalated. Despite using orthoses successfully for 4 years. I deduced the shoe caused the final damage whereas before such damage was controlled. The neuroma was injected with steroid and local anaesthetic which yielded no benefit and ultrasound showed a lesion in the third intermetatarsal space. Too little, too late!

Injury leading to haematoma can theoretically cause scarring with the same fibroblastic pathogenesis unless haematomas are resolved. few patients encounter treatment early enough to avert such problems.

Spasms of the interossei are not reported in the literature, but again my own foot suffers from paroxysmal spasms that are inordinately painful. These small muscles, be they lumbricals or interossei seem innocuous but could contribute to compression, or because of nerve damage and nociceptor influence increase axonal transport signals. The presence of a bursa is not an uncommon finding as most foot surgeons will report and without histology, we make blind assumptions as tissue cannot always be classified at the time of surgery without the aid of a dedicated histologist or cytologist. In my own case list, I recorded and stored some 300 reports (1993-2001) of which just under 100 related to a neuroma; 13% were mixed neuroma-bursa and 9% were bursae lesions alone. A further 13% were undiagnosed lesions thought to cause pain. As time progressed with improved MRI and ultrasound the undiagnosed lesions reduced with the refinement of the pre-surgical screen methods.

Junction box theory

Type II Govsa (2005) 20% of cases n=50. Communicating branch between the lateral and medial plantar nerve

Not all PDNs are caused by footwear as injury, either directed at the sole, or through a fall or twist affecting the metatarsals can incite the same changes; bleeding, hematomas, scar tissue can still exert influence on localised structures, but some form of adjunctive compression force will exacerbate symptoms and pathology.

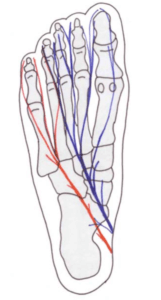

The idea that metatarsals 2-4 are mobile and are the cause of excessive movement arises has more validity. The anatomical relationship around the connecting branch between the medial and lateral plantar nerve promotes a potential obstructive impingement if damaged. I have termed this the junction box theory.

Govsa’s (2005) classification of anatomical communicating nerve branches is persuasive where there were only 28% of his 50 male specimens had a communicating branch between the lateral and medial nerve. In 8% of cases, a branch from the medial nerve toward the lateral nerve ends in a junction box between the 4th-5th metatarsals. We know that the incidence of 4th interspace neuromata arises between 2-8% of the time (Raouf 2019, Bencardino, 2000, DiCaprio 2018) and the first space is hardly ever recorded. So why is the 3rd space more prone to symptoms and change than the 4th space. The independence of the 1st and 5th rays are almost part of basic podiatric-orthopaedic foot knowledge and so can move out of the way compared to the central 3 metatarsals. Naraghi (2017) were unable to demonstrate any relationship in this study between radiographic metatarsal length and angular measurements for symptomatic PDN when compared to a control group.

Why is the second interspace is less frequently affected?

In regard to the presence of 15-25% of lesions being located between the 2/3rd metatarsals, we can only make some suggestions. There is no junction box presumed. Govsa’s cases were still small and might not be applicable to a large population and the samples were male. The supinatory effects on the 3/4th metatarsals and their intermetatarsal space, at the time of the propulsive phase, are greater than the forces between 2/3rd. Others might argue that pronation causes a neuroma but these theories have yet to be investigated. Kilmartin used a felt insole to create both supination and pronation and found no difference in neuroma pain.

The other factor that comes into play is the combined effects associated with a broad foot. While the 2/3rd neuroma does exist without additional forefoot deformity, many patients have an attendant hallux valgus, and others hammered or subluxing 2nd MTPJ. The compression effect might be considered more relevant as foot surgeons often deal with multiple problems together.

Diagnostics

False diagnoses

There are perhaps two fundamental questions clinicians would desire. Is the test accurate and which test should I use? As a clinician, I can advise that I have undertaken an MRI scan for a neuroma and the result as reported by a musculoskeletal radiologist was negative. I decided to operate and found a neuroma. This is never an easy decision but highlights the reality of false negatives. An orthopaedic colleague swore by MRI while I placed most of my own faith on ultrasound (US). Which one of us was right?

Key imaging techniques

Santiago (2018) points out that a nerve 1mm at the level of the intermetatarsal heads can be determined on high US and MRI.

Ultrasound is more difficult to read in static form compared to dynamic states and so is dependent on experience from the operator. The position of the transducer head and the quality of the equipment can make a difference. As technology has improved the growing inclusion of ultrasound has grown exponentially in podiatry. Many favour a plantar approach. A well-defined round or ovoid area is seen on the short axis, while on the long axis a fusiform shape is evident for a neuroma. The term hypoechoic is applied relative to the adjacent tissues. If injected the area distends where a bursa is present. Lesions longer than 20mm should be excluded as unlikely PDN lesions (Santiago).

Magnetic resonance imaging is more expensive and time-consuming but less reliant on the operator, although carried out by trained professionals nonetheless. A well-demarcated ovoid or dumbbell-shaped intermetatarsal mass is evident. T1 and T2 weighted scans show a low signal for a neuroma. Gadolinium is injected to improve the quality of the image and only enhances a bursa rather than the PDN. T2 is hyperintense while T1 is isointense for the bursa. The MRI provides better soft tissue differentiation and visualisation.

Sensitivity & specificity

Sensitivity relates to how often a test shows positive i.e true positivity (TP) as opposed to a false negative (FN); this was the case cited above in my own experience with the MRI result. TP/TP+FN=sensitivity.

Specificity is where a person does not have the disease and the calculation is related to how often the test turns out negative or represented by a true negative (TN). If you have a test as in the case of the MRI and it shows positive then you have the condition but it could be a false positive (FP). TN/TN+FP=specificity.

| Sensitivity | MRI | US |

| Xu | 93% | 90% |

| Bignotti | 90% | 91% |

| Claassen | 84% | – |

| Benecardino | 100% | 98% |

| Pastides | 88% | 98% |

| Raouf | 80% | 93% |

| Specificity | MRI | US |

| Xu | 68% | 88% |

| Bignotti | 100% | 85% |

| Claassen | 33% | – |

| Benecardino | 68% | – |

| Pastides | – | – |

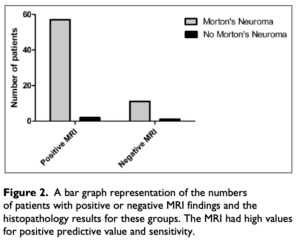

Claassen’s sensitivity graph (below) helps visualise data from the perspective of true positive and true negative.

Claassen (2014) Role of MRI in neuroma

Bignotti (2015) looked at past papers in order to run a systematic review (meta-analysis) comparing MRI (3 studies) to ultrasound (US) for 5 PDN studies. Sensitivity and specificity were criteria important. Of 277 studies they narrowed the group down to 27 papers from which 14 articles were selected. Six studies were prospective and eight were retrospective.

In their meta-analysis Bignotti et al concluded that there was only a small margin of difference in terms of sensitivity, both being highly sensitive. This paper suggests that at the time of the review, MRI and US are equally accurate, the US has more advantages in the cost.

Claassen (2014) highlighted the use of MRI alone and found negative MRI when Morton’s neuroma existed (Figure 2). This meant specificity was poorer compared to sensitivity. In this case, the authors based in Germany felt clinical signs of PDN could be more reliable.

The value associated with imaging excludes differential diagnoses. Pastides (2012) found sensitivity high for US compared to MRI and concluded that in the presence of clear clinical signs imaging was not required. As with other authors, there were indications for ruling out other problems or determining foot problems with more than a single PDN. Xu (2015) concluded that the US could provide better accuracy than MRI. Some 7 years earlier a study by Lee (2007) contradicted this finding suggesting both imaging methods were equal. Bignotti draws the same conclusion with their 14 articles comparative meta-analysis.

In order to answer the question Which one of us was right? – there is no absolute correct approach presently even though these reports come from an online search (30/10/21). Cost and flexibility must be considered as well as the confidence surrounding the presenting symptoms. For the clinician intended conservative care for a measured time for review, imaging is not necessary but if this fails then injection therapy or surgical management should have a baseline imaging method applied to measure the size and exclude differential causes.

available from Amazon books as an ebook or paperback for patients and students set at an easy understanding level

Continuing reading the series on the plantar digital neuroma on ConsultingFootPain. Why not read the third article The Discredited management of Morton’s Neuroma

![]()

A full set of references is available to click here

Thanks for reading ‘Digital Neuroma Old Problem New Analysis’ by David R Tollafield

Sign-up for here my regular FREE newsfeed

Published by Busypencilcase Communications. Est. 2015 for ConsultingFootPain

Recent Comments