Pathways and Approaches for Plantar digital neuroma

Protocols, Guidelines and algorithms for Morton’s Neuroma

The unsung and discredited management of Morton’s Neuroma exists because not all pain (metatarsalgia) is in fact Morton’s neuroma but a product of misunderstood pathology. Discredited is associated with insufficient research of a standard that can prove or disprove that such care works or fails.

Download your free clinical neuroma guide

In this third article within the series plantar digital neuroma, we must understand that treatment success is based upon timely intervention. Acting before pathology has changed the biomechanical and chemical properties around the nerve system at a point where digital nerve branches are exposed to compressive forces.

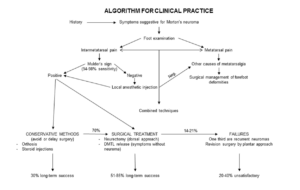

Click here for the neuroma algorithm – DiCaprio 2018

This is the third article in my new series covering plantar digital neuroma (PDN) for professionals and those interested in approaching this problem. This is the fifth most common foot condition seen in foot surgery (PASCOM 2021 data). Protocols require some latitude but the simplest approach is conservative – non-surgery (injections or similar) – surgery. The aim is to manage most by conservative care.

Cautionary tale

The literature informs us that neuroma lesions if enlarged beyond 5-7mm do less well from steroid injection management and changes in pathology around the nerve bundles reduce neuron effectiveness (Makki 2012). Raouf (2019) suggests the cut-off point is <6.3mm while Benecardino (2000) points out that lesions of 10mm found on routine MRI can be asymptomatic. The algorithm is based around conservative and steroid injections. While surgery implies cutting out the nerve there are some types of injection being explored such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryosurgical ablation which are quasi surgical because small incisions and probing into the tissue to create thermal changes arise. Only RFA carries investigation by NICE at the time of writing.

Protocols should be based on absolutes; for example, they fit ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT schemes where some degree of automaticity is important as part of efficiency. Unfortunately, PDN does not appear simple, although Di Caprio (2018) sets out one algorithm from their literature search (above). There is an undefined period where symptoms will raise a few suspicions for the patient. Even early signs will be ignored unless there is a ‘break through’ with the discomfort that can be registered as pain and inconvenience, i.e. the number of times someone has to stop to take their shoe off to rub their foot. Matthews (2019) concludes their meta-analysis report with the statement, ‘…no high-quality evidence currently exists to inform intervention should be the gold standard for first or second-line non-surgical treatments.’ We turn to a 1995 paper when Bennett published the first idea of staging.

Conservative care & Bennett’s seminal paper

In 1995 Gordon Bennett published one of the first papers showing staged management and its effect over time. This sequence could provide a baseline algorithm or set of rules to guide rather than mandate an action. The first stage was conservative care which comprised footwear advice and insole, orthotic, and footpads. Manipulation and reflexology were not included. Non-invasive injection of a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) and lastly, surgical excision of the neuroma. The patient would present with a variety of symptoms, as illustrated in the table below, representing 115 patients. More than one choice could be made.

| Pain in front of the foot | 87 | 76% |

| Pain relief with shoe removal | 69 | 60% |

| Pain between toes | 50 | 43% |

| Inability to wear fashionable shoes | 45 | 39% |

| Numbness or tingling in toes | 26 | 23% |

| Pain at rest | 22 | 19% |

| Pain radiating from foot into leg | 13 | 11% |

| Pain at night | 11 | 10% |

| Pain in the entire foot | 10 | 9% |

Bennett et al 1995

Memory and the poor historian

All clinicians appreciate that the quality of a patient’s historical memory can be unreliable, or at least until the patient recognises that a problem exists. Pain breaks through the daily routine, affects certain footwear, keeps someone awake at night, and all bear the hallmarks of significant interruption. The grey area around recall remains during an unaccountable period before the patient can recognise some of the above 9 types of pain or sensation change in order to seek help.

Initial symptoms are vague

The earliest signs from my own neuroma experience involve occasional and infrequent twinges. An occasional irritation could confer paraesthesia. Discomfort in the general area. These symptoms are blocked by busy daily routines and inconsistency. At this point, any test could well prove non-existent. An ultrasound would show a little size increase. Deep thumb-forefinger pressure might well evoke some discomfort, but Mulder’s click would be negative as would most other problems. I found the use of a blood pressure aneroid sphygmomanometer to be invaluable for the collateral compression test. For this to be positive, i.e pain arises below 100mmHg, the neuroma has to be advanced.

Approaching the patient

A thorough understanding of pathology is required to present the patient with a comprehensive programme that they can introduce. Footwear, a poignant compression feature, should be changed or modified in fit, and design with special attention to the forefoot and heel. Thirty-nine per cent of Bennett’s cases noted fashionable shoes, and 60% found relief when removing shoes. Morton, in his original works, recorded five of twelve patients who attributed their problems to footwear.

The use of orthoses and metatarsal pads have long been a method used to assist forefoot pain in orthopaedics and podiatry, with the metatarsal pad and raised insole below the arch being key designs. On the other hand, Bennett found 47/115 patients (41%) improved with shoe modification. In addition, the timeline associated with symptoms suggested 43% of those suffering under 12 months improved and 38% improved where symptoms lasted longer than 1 year.

Poor evidence

In searching the literature, a lack of evidence exists to demonstrate the value of orthotic management. Albano (2021) used only 20 patients applying ultrasound (US) to evaluate custom made orthoses for plantar foot pain, but 81% (22) had intermetatarsal bursitis, and only 3 patients had Morton’s neuroma.

Dominquez (2020) looked at physical therapy. While describing toe stretching and deep pressure, this was a single case and follow up was only 2 months. The most helpful comment referred to a citation from a different paper highlighting inflammatory mediators and peripheral nociceptors could be helped by mechanical stimulus. Patient compliance with exercises was noted. On a personal note, a patient who was operated on for neuroma found post-operative discomfort until she decided to seek reflexology (manipulation therapy) unilaterally. Her success was positive, but the experience was painful.

Matthew (2019) carried out a systematic review looking at non-surgical interventions. Citing a chiropractic paper (Govender, 2007) using a single-blinded trial with manipulation and mobilisation again revealed a short follow up time, but this mode of management might reduce pain by breaking down the connective tissue. Applied to dermal-epidermal post-operative scar tissue, this seems to have value. Matthews concluded that ‘no studies assessing the effect of orthoses on foot function related to MN were found by the review.’

Valisena (2007) reviewed one paper associated with orthoses out of 29 papers and filtered the selection down from 283 titles for not meeting the criteria e.g prospective, retrospective and random controls (RCT). Thompson (2020) undertook a systematic review 13 years later focusing on non-surgical treatment for Morton’s neuroma. Orthoses occupied a short paragraph citing Kilmartin (2006) but for their small sample of 23. Again only a short follow up period arose, with 28% of patients going to surgery. Kilmartin’s paper was the only review by Valisena for orthoses. While designed to effective research standards, the podiatric paper looked at the theoretical use of the cobra felt wedging for neuroma patients and proved that this method of modification was ineffective. No such paper has been followed up to look at bespoke orthoses with the credentials of a prospective high-level RCT study. Valisena concludes that for RCT, better results were shown for invasive treatment.

Saygi (2005) used combined strategies of footwear modification with orthoses and corticosteroid injection as two groups. There was no statistical difference between groups, although the results for a cohort of 82 patients are shown below having being followed for 12 months. Di Caprio (2018) points out conservative care offers around 30% sustained benefit from a literature search.

| Follow up | Group 1 | Group 2 |

| 4 weeks | 23% | 50% |

| 6 months | 28.6% | 73.5% |

| 12 months | 11% | 82% |

Saygi 2018 Group 1 insoles alone and Group 2 insoles + steroid injection.

We lean on clinical evidence heavily and the use of meta-analysis (MTA). While important MTA can exclude some pearls that can guide development. When it comes to conservative care, only orthoses are reviewed in detail and followed up for short periods. They contain insufficient numbers in the studies.

Manipulation is certainly important and yet again suffers the same study design problems. Valisena is correct in desiring random controls as this is the gold standard, whether by pro or retrospective study designs. Case histories are important to drive studies, so my own experience with a bespoke orthosis was positive for 4 years, but further compressive damage from a tight cycle shoe advanced existing damage. It increased the size of the neuroma to a higher symptomatic level. The absence of quality studies remain a problem. Those that exist can only act as pilot studies at best; at worst, they are inconclusive and suggest conservative care does not have a value against other methods. However, applied to the timeline correctly conservative care does work. For this reason, Bennett’s paper remains important because it provides a sense that conservative care can be of value, as shown by his evidence that 39% of a cohort of 115 benefitted beyond 1 year. However, the research was retrospective over 3-4 years and would have to be considered of a lower scientific level of evidence.

The unsung and discredited management of Morton’s Neuroma is not that treatment cannot work but that in many cases some treatment regimens are too late to arrest the significant changes associated with nerve pathology. Podiatry needs to change its approach to providing advice and become more proactive now that many clinicians use ultrasound.

Now available from Amazon books as an ebook and paperback. Set at an easy understanding level for patients

Thanks for reading my series on plantar digital neuroma “The unsung and discredited management of Morton’s Neuroma,” by David R Tollafield

why not read the fourth article Management pathways for Morton’s Neuroma

Sign-up for here my regular FREE newsfeed

Published by Busypencilcase Communications. Est. 2015 for ConsultingFootPain

Recent Comments