Colour, diagnosis and training in podiatry

It’s a tough question, and the focus is on diagnosis, colour and training. Not so much to answer the question, ‘was I trained with colour in mind?‘ but have I done anything about having a deficit in my knowledge associated with skin variations. The question was posed by my colleague Jill Halstead-Rastrick. Clearly the medical professional have been waking up, but have we in podiatry? After all we are only dealing with feet aren’t we? In fact, the matter does not fall to being racist, but more about being ignorant. Perhaps instead of this suggestive slur we might want to replace ignorant with unaware! As reflective practitioners we only learn about life when we experience life for ourselves.

In this second article covering racism, I now explore the subject of skin colour associated with diagnosis in feet. The problem with skin pigment created by the density of melanin within the deeper layers of the top layer of skin (epidermis) is that colour erroneously suggests our identity of origin. Following my interview with Jill Halstead-Rastrick (link) in June I wanted to explore her concerns. These encompassed the thoughts and passion around Black, Asian and Minority Ethnicity (BAME). I had challenged my own ideas of racism toward colour (the melting pot).

Reading score = 52 (technical)

Challenging skin colour presumptions

Dr Halstead-Rastrick was able cite a case concerning a medical student’s lack of confidence in diagnosing dermatological issues in black people. The temperature has turned up on this subject with newspaper reports and radio interviews. headlines such as ‘ Watching for patients going blue is racist, says University!’ The quote comes from the Daily Telegraph. One recognises the technique to call to action the reader with such pithy words. Redness is less apparent as a cardinal sign in darker skins. If the medical profession have woken up to the flaws in training it is as much down to students like second year Malone Mukwende, studying at St George’s, University of London. The need to reinforce teaching clinical skills on black and brown skin was evident as he felt he had not been trained to spot a number of medical conditions. Dr Joseph Hartland from the University of Bristol Medical School used the example of patients turning blue if short of breath, a sign which does not show up as readily in people with dark skin.

Wolfe Medical Atlases although popular and contained diagnostic skin variants often had insufficient colour distinctions

Photography & Textbooks

On the face of such evidence one can well understand that without exposure and guidance dermatological conditions can floor the best. The use of modern dermoscopy is starting to take away some of the guesswork. In truth dermatological features deal with redness, swelling, borders, symmetry and pigment. White background colour helps identification better in some ways because the contrast of lighter tones aids diagnosis. The representation of lesions in books might well be predominantly white because publishers often prefer this contrast. Colour plates are still expensive and can be frugally used in medical texts. As far as photographers are concerned, colour of any kind can be catered for. However, there is no reason why darker skin cannot be represented. As we grasp the issues of colour within society this lack of image must change. Jill has a special interest in this area and added comments to a Twitter debate suggesting white racial bias in medical texts.

I looked at two texts I was involved with for podiatry and only the first, ‘Assessment of the Lower Limb’ (Merriman & Tollafield 1995) had a colour inset. This had no black coloured feet. The co-authors did not submit cases with colour and as an editor I was ignorant of this omission back in 1992-3 when the book was completed. The later edition Merriman & Turner has no colour inset at all. Clearly we had been ignorant of the importance of colour bias. I suppose if I had a statue it might well be in peril!

Books commonly use black and white format. I know our publishers were tetchy about the overuse of colour and my first two paperbacks cost the reader more in print than had they been in black and white. In the self-publishing market called INDIE publishing, colour can bump the jacket price up and so black and white is still popular.

Texts back in my graduate days

Photography can cater for contrast. My own dermatology bible was a Colour Atlas of Dermatology by Levene and Calnan (1974). The text was all in colour and yet showed only one darker pigmented person. This was partly obfuscated by the fact it related to gravitational eczema. At best this was in a Mediterranean pigmented skin. Does Dr Halstead-Rastrick’s challenge hold true? Going to Zatouroff’s Physical Signs in General Medicine, Zatouroff spent a good part of his career on the African continent. Our medical lectures with this medical physician were reinforced with colour 35mm slides representing diseases that predominated in Africa but had been eradicated in the UK. His Colour Atlas Physical Signs in General Medicine, like the dermatology text, came from the stable of Wolfe Publishers. Of interest Zatouroff even had a section on calluses.

Dermatology and Dark Skin

The medical student who worried about dermatology would make up for any dearth in that respect by using his knowledge of general signs of cirrhosis. The membranes of black and other skin colour are not so difficult to contrast compared to the epidermis. A full history and physical examination is required. It is doubtful the student Dr Halstead-Rastrick cites would be exonerated for missing other signs of liver disease. The jaundiced colour would be different but the sclera could still yield information and of course palpation, the presence of ascites and auscultations of the gastro-intestinal system and lungs. CT scans and blood tests would offer confirmatory diagnoses. My argument here is to value a balance in any discussion and not take a view that missing signs can always be down to an absence of poor teaching in medicine.

Problems associated with photography

However, language does impact on the clinician as this is part of history taking. Experience is often the only way any clinician develops and to do this we have to have exposure. Zatouroff’s own knowledge of rarer medical disease helped his Harley Street practice and his mainly Middle-Eastern clientele were indeed wealthy. Overcoming much of the textbook problems can be met by the internet as we do not have the same publishing concerns. There is a big BUT though, clinical photography has suffered a change, in some ways for the better and some ways for the worse. Protection against unlawful publishing has led to restrictions of photographs. Where I once kept a camera by my side in clinic, taking photos within the NHS has become regulated more and more. Medical photography is costed out for departments and not accessible for podiatry. Community access is poorer than that enjoyed by the acute sector. Patients taking their own photos for our use is often a way around this dilemma but permission to publish is essential.

Skin cancers are less common in black skin which makes sense as this is what melanin does, protects the deeper layers from skin damage. When it comes to psoriasis, the similarities to lighter skin are not so different. Pictures of psoriasis can be found on the internet sites such as medical news today. As the internet becomes more accepted, there is no reason why people cannot access pictures of skin lesions. Of course there is a debate about sensitivity around the idea of illustration being gory but reputable sites exist.

When Covid-19 struck, the lesions on toes caused us greatest concern. In a recent publication by McFarling (July 2020) lack of darker skin in textbooks points to the same criticisms highlighted by Jill Halstead-Rastrick. One of the points McFarling makes is that Black, Asian and Minority groups suffer the consequences more than Caucasians and yet there is a paucity of dermatology textual information. With the media awareness around Black Lives Matter it is more than likely that there will be correction of this absence. This should occur as we are all escalating our own awareness of any differences between groups. Of course we must add that Covid-19 has taxed both the scientific community and medicine and we are still learning.

Corns and callus

By the time I was qualified and practising, I noticed that my Asian patients had a greater propensity to corns that seemed intractable. As far as pain was concerned, enucleation was poorly tolerated in this group. Their pain tolerance appeared much worse than my caucasian patients. I was not taught this but found it out for myself. There are now plenty of papers to reinforce the view that there are differences between people of race, ethnicity, and culture

Race, ethnicity, and culture are terms commonly used with similar characteristics and subtle differences. The term “Race” refers to a classification based on an individual’s physical appearance with skin color as the most prominent determinant. “Ethnicity” is fluid and depends on context, incorporating the notions of a shared social, cultural, or religious background that is distinct and passed on between generations leading to a shared identity. A range of definitions exists for “Culture,” which can be described as the repeated behavioral responses in society with social, religious, intellectual, and artistic influences. For this review, the most commonly used terms in the literature “Ethnicity” and “Culture” will be viewed as synonyms.

The quotation from above comes from “The Relationship Between Ethnicity and the Pain Experience of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review” by Wingfai Wok and Thakshyanee Bhuvanakrishna (2014).

As far as debridement is concerned the podiatrist must determine the absolute depth to debride safely. Once the surface has been reduced the colour is less pigmented. The learning curve is steep but does not take long to understand how to differentiate depth of debridement for different levels of skin darkness. The literature covering corns and callus in all groups is particularly impoverished though within the field of podiatry. This appeared evident when publishing my own results following my MSc thesis in 2016. My case examples were white thus confirming Jill’s criticisms covering research.

Pressure marks are often identified because the pigment lessens especially on the medial and dorsal aspect of feet. The talar head callosity can be seen in any patient and is typically related to the cross legged sitting stance where a flexible foot exposes this part of the anatomy. Rubbing follows with thickening.

Mysteries of Injury and Keloid

Taught from an early part of my career that ‘black skin’ suffers from a thick scar condition is often described as worm like. In a 2012 USA study this statement has been confirmed. The incidence from head and neck surgery was 0.8% in African-American skin compared with Caucasian around 0.1% incidence. One of my favourite sites is the NHS. It has simplicity and is unbiased. Taken from an NHS source covering keloid, both white and darker skin are contrasted.

As a podiatric foot surgeon working in both sectors, I have operated on all types of skin colour. Indeed, African and West Indian skin do scar but keloid is not that common in feet. However, I have in fact seen keloid more frequently in caucasian skin. The case of a tendon lengthening in an adolescent girl was notable for both legs. On one occasion I used a plastic surgeon for a thickened scar after a revision bunion surgery in an 18-year-old. The younger patient is far more liable to suffer keloid in my own experience than mature skin. In truth I would advise all patients to be informed about keloid and not use colour as a misrepresentation. I would add that surgery should not be revised without a second opinion from a plastic surgeon. The opinion is to reassure the patient rather than promise surgery. Additional skin insult will usually make matters worse not better. Keloid scars often settle over a two-year period. Conservative care alone is usually required as in creams and compression gels.

Infection is more often the cause of scarring. Foreign materials and tribal scaring is well known in South America and Africa as well as Australasia. As part of tattooing, some tribes deliberately damage the skin by enhancing the repair to make the effect more notable. That a keloid forms is not unusual and if a greater density of melanin predisposes keloid then the USA study supports the greater frequency. Any podiatrist believing caucasian keloid is rare will need to be reminded that this is not true.

Deformity and Foot Shape

This article emphasises some of the variants associated with darker pigmented skin as a dermatological feature. When it comes to shape, all races experience foot deformity. The cultural custom of binding female feet in China seems abhorrent and was related to the Imperial Dynasties and called Lotus Feet. It was a mark of beauty and has fortunately all but died out. The humble bunion and hammer toe exists, the former even in unshod feet. One condition that might confuse anyone is the flat foot. All groups have low arches and the relationship between a low arch does not equate to a condition necessitating treatment.

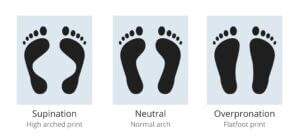

Shape as illustrated is no indicator of true foot problems

The propensity of Africo-Carribbeans to have low arches is high. The calcaneal pitch has long been studied by podiatrists. The pitch is the angle that the calcaneus makes with the floor and varies from 15-30 degrees. A low pitch reduces the arch height and vica versa. The high pitch makes the foot more cavoid in shape. The flat shape does not impede sports and so the discerning podiatrist is left with using careful assessment of the foot to distinguish between normal and abnormal variants.

calcaneal pitch. Courtesy CCPM 1981

The obsession with arch height has always been confusing for the public who are often left with the belief that and arch support is warranted. As long as conditions such as posterior tibial tendon dysfunction and midfoot problems can be ruled out, often the shape needs no attention. Preidt (2010), an Ontario based writer, published an article contrasting the features between colour and based upon a North Carolina study.

FRIDAY, Nov. 12, 2010 (HealthDay News) — Black Americans are more likely than whites to have common foot disorders such as flat feet and corns, new research shows. In the study, researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill examined the feet of 1,536 volunteers and found that blacks aged 45 and older were three times more likely than whites of the same age to have corns or flat feet. Among people who were not obese, blacks were twice as likely to have bunions and hammer toes. However, no significant differences by race were found for these two conditions among obese people. (Robert Preidt)

Is there a conclusion?

The title was ‘Colour, diagnosis and training in podiatry?’ Dr Halstead-Rastrick challenges this in the context of teaching podiatry and medical students. Our educational institutions may not highlight the distinguishing features that make one race or ethnic group stand out. We don’t want, neither do we need, a group to stand out. What is required to understand variations that ensure we manage foot conditions in a way that is tailored to a patient’s need. To do this we do need to be exposed to as many tones of colour and lesions as possible. We need to study case histories so that we can contrast conditions that yield an effective outcome. There can be no doubt an incident in Minnesota has done more to challenge our attitudes in a wider arena than medicine. That podiatrists are part of the medical model therefore must recognise disease changes with race and ethnicity from thalassaemia, typified by those people from areas such as the Mediterranean, south Asia, southeast Asia and Middle East, to sickle cell disease typified by African origins. Lowth and Jackson provide a wide range of examples in their paper on Diseases and Different Ethnic Groups (2015).

Personally my view is that we were not trained with colour in mind, but we were trained to look at feet and work out variations through experience. Even if we did concentrate on one group, there is wide variation within the caucasian coloured skin which itself has different tones. It is hard to imagine that clientele in areas such as Birmingham, London and Manchester do not have large groups of ethnic variation. However, some colleagues may be exposed less than others and so education is the responsibility of us all.

Making your own mind up

It is for the reader to decide their own view on the relationship of colour to their own experience at college, university and in practice. Whatever your personal views there is no doubt that a good practitioner takes a good history and is capable of researching any deficits. After all, why did we change from diploma to degree status. We should be arming our future practitioners with the ability to think outside the box, or to expand on their life long journey where constant learning has been accepted.

Thanks for reading ‘Were We Trained with Colour In Mind?’ by David R Tollafield

This article is the third in a short series on BAME produced for ConsultingFootPain

Published by Busypencilcase Reflective Communications Est. 2015

November 9th 2020

Recent Comments