Caught Out with Cancer

When Your Patient Paints a Rosier Picture Than Ideal – Sartorial-Misleading-Articulate

Cancer is something that affects any part of the body, but being caught out may not always be the doctor’s fault. In this article, I am using the abbreviation ‘S.M.ART’, which will be explained at the end. But how should we view being ‘fooled by the story of my father’s sudden death from bowel cancer? Who was to blame? I know we are on a foot health site, but believe it or not, as a foot specialist, my medical training and experience required me to know a fair bit about bowels. Foot cancers are rare, fortunately. In some ways, I was obsessed with my father’s bowels, but usually other people’s bowels. The subject of this article covers a common primary cancer site, the colon. Secondary sites can include foot cancer, but these are very rare.

An Independent man

My father had lived alone and was fiercely independent. The cause of death was metastatic carcinomatosis, cancer of the colon and bronchopneumonia. Could my father’s death have been managed better? Was the medical service incompetent, ignorant, or overwhelmed by the coronavirus, or was this the patient’s or relatives’ fault? These became both the question and the narrative that followed this widower. He had lost an enormous amount of weight over the previous 5 months. Lockdown No. 1 finished, and so I was reunited with my father. I took him to see his GP as something was nagging me. His loss of weight, for one. It was July (2020).

We went through the COVID-19 routine. The ‘practice bouncer’ let us in after checking we were bona fide. The GP had spoken earlier to both of us by phone and felt a need to examine my father. I had persuaded my father that I needed to attend.

“Could he climb stairs,” the GP asked.

“Yes,” he replied.

“No,” I said.

He would have once. Now, much weaker, he had lost that inner strength. He walked differently, no longer upright. He leaned forward, arms positioned backwards like jet aircraft redolent of a young child running around a school playground. He had fallen on one occasion, tearing an ear lobe, necessitating stitching. His letters were flowery and prolific. His GP later told me he had written over a hundred query letters. He had never been approached over this effusive production. The doctor’s surgery was his second home. If letters did not appear by post, his telephone calls were equally frequent.

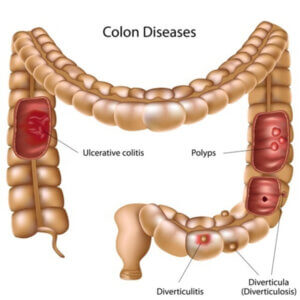

Inflammatory bowels

https://www.shutterstock.com/g/alila

Bowels were a constant subject when we talked on the phone and FaceTime. Estranged by the first lockdown and distance (I lived 200 miles away), he spoke to me in great detail. Bowels came up, as did the frequent subject of blood tests. I talked about Bristol faecal chart shapes. His faeces had been abnormal for a long time. The dual description of constipation and diarrhoea made no sense. I needed to know why he was taking so many laxatives and find out why his weight had fallen. He kept me at arm’s length but continued the tale at every phone call. He misled the doctor about his weight, saying that it dropped after his wife died. That was 8 years ago. His usual appetite was huge, but we noticed that he was no longer able to consume the three courses he usually devoured. We could go nowhere unless he were up early to use the bathroom because, on one occasion, he had become incontinent. After this one event, his social landscape closed down. The toilet was splashed with remnants of loose evacuations. He could not see his efforts because of his failing sight due to aged macular degeneration. The array of laxatives grew, and he then switched to buy over-the-counter brands. This constant use worried us. The practice went along with this and had, in fact, sent him off a year earlier to have a gastroenterology consultation. The flexiscope could not enter his transverse colon due to pain. And the July appointment with the doctor was finally achieved after much cajoling. The intent was to find out what was being said about his abnormal bowel habits and question the use of laxatives. Diverticulitis was diagnosed some years ago, and this stuck. The label fits everyone’s comfort needs in the absence of anything else.

The Surgery Consultation

“Surely this isn’t normal,” I asked his GP after his physical examination, which raised no suspicions apart from the odd pain, which he played down! The doctor was pressed for time, having fitted his father in at short notice.

“At 92, I’m not worried about your father taking laxatives, but he should cut back if he can.”

As far as the temazepam (the nighttime sedative) was concerned, addiction was not a concern at his age. Father had doubled the dosage. His sleep patterns had deteriorated. An appointment for a scan was delayed. The GP could do nothing to expedite this. It was clear the GP could not go against his wishes, and the laxative story or loss of weight remained unchallenged. He fell that night after we returned from a meal that he had struggled with (see my article on falls). It was one of his pleasures. The pain continued, as did the laxatives, but they were not helping. A prescription of the antispasmodic buscapan was issued. He then accused the doctor of reckless prescribing after he became weak and disorientated from this drug whilst heading off to town on his oversized motability scooter. After all, he could have wrecked his motability scooter; he pointed out! He assured the doctor (on this occasion) that he would take matters no further. Everyone saw him as that quaint old man who went out every day dressed as a gentleman dressed in a jacket, shirt and tie. The trip to town was the final straw. It took no expert to see that he was desperately ill and common sense judgement was being affected.

Too ill to attend the surgery

Father arranged another appointment with the surgery. Relations between father and daughter had deteriorated, hence my lateness on the scene, as we had a respite during the Covid lockdowns. Distressed and in tears and at the end of her tether I had dropped everything and drove to join my sister late on the night before his GP consultation. We both turned up and after taking one look at my father, I rang the practice, saying he was not well enough to attend. A GP attended him at home, performed an internal and put his problem down to constipation. I looked at the stomach, loss of weight, no appetite, weakness and occasional breathing difficulty. This man was dangerously ill and had ascites and writhed in pain as it came in spasms. The central heating blasted out at 30C. He shivered while we had to strip off. Despite the lame diagnosis, the GP agreed to admit him to the hospital.

Attending hospital with my sibling, we pushed him in the hospital wheelchair out of the deteriorating weather into the triage station, a portacabin, after making a nuisance. Even a lady with her child thought it poor that this feeble man was having to wait, exposed to the cold as he shivered. He was finally in, and we were relieved, But then he was discharged Wednesday – only two days later. There was no care plan and no diagnosis. The original scan that had been delayed was undertaken. There was still no diagnosis despite having been exposed to all the experts and consultants in a general hospital. Worse still, there was no feedback. I remonstrated and refused to have him home, as there was no care package. By now, I had not been home for 4 days. Neither my sister nor I could cope. He was an intensely difficult man who could not wait to leave the hospital and became angry at the slightest suggestion that he could not manage by himself. It was clear that he couldn’t cope any longer or apply any rationality to his ever-increasing confusion. Confused and the elderly should not be mixed up with senility. This man was never senile. I spoke to yet another doctor at the surgery. Curiously, the GP had been troubled by the father’s early discharge in the face of elevated blood markers. These are the markers that show inflammatory activity and infection. What we didn’t know was that his potassium levels were rising, and the kidneys were shutting down. The answer to the confusion lay in these changes. Some cardiac enzymes had been elevated a month earlier but had been dismissed after he had been sent to the hospital by his practice for hip pain. These trips yielded no diagnosis and exhausted him.

After his premature discharge. Haematoma right arm. Ascites visible. Weight loss over two stones

Further deterioration

After his premature hospital discharge, we were now on Thursday, having forcibly delayed his earlier discharge the day before. We settled him down for bed. I dressed him while my sister warmed some soup up, which he barely managed. The following day, he was in trouble, so we raced across from my sister’s house, having left him around 8 pm the previous night. I found he had coughed up blood all down his pyjamas. Tell-tale coffee granules spilt down the side of a yellow bucket. With the aid of 111 and the on-call doctor, we had him ambulance back to the hospital. It took three paramedics to move him. The 111 doctors had prior experience with end-of-life patients. Her eyes connected with mine. She mentioned the word cancer. Father was confused. ‘No, I’ve been tested for that.’ He was told he was dying. ‘Was I too direct, do you think,’ the doctor asked me later. ‘No. You were perfect,’ I replied. I had kneeled to make him understand. Through a choked voice, I could barely hold back from breaking down, and I told him if he went to the hospital, he would not come out.

Finally, I had someone taking notice. My diagnosis was not wrong, and I cursed the politeness instilled in me by my father, who now relied on my judgment. Over the next 48 hours, he slipped away. Not seeing him at the end was the cruellest stroke, which still haunts me. A scared man who could only speak by mobile phone until his phone battery died. He fell out of bed in those last days, entangled by tubes. My daughter ( a hospital sister) phoned in to get help while I kept him on the line. He made no sense, was weak, and could barely talk. What he said was confusing. In the next 24 hours, calls to the hospital were unhelpful, delayed and ignored. The family were as isolated as our father. Two days after his final admission, a ward doctor sounded near to tears as she gave me the news. Dad had died. We had agreed on a DNR, but this was delayed and arrived the day after he died. They tried the cardiac paddles three times! I shivered at the thought of his ribs cracking. He could not even lie or sit on the hard ambulance trolley as his rump had lost all fat.

Happier times with his daughter-in-law & son July 2019

Reflection

In the cold light of day, as a clinician and not a son, I needed to make a decision. I spoke to the GPs, who were, on the whole, caring. I understood the pressures of practice. I have worked within the NHS for 40 years. This was a case of SMART misdiagnosis I decided having constructed the unlikely scenario and an acronym to fit. S-M-ART means Sartorial-Misleading–Articulate. Since last November, the medical profession has been guided to follow the patient’s wishes in decision-making. This is generally a good policy. However, the SMART patient creates the outlier. The previous history shows that we were all misled, and the family believed all was being managed, albeit slowly. Father’s accounts were diluted, and he could always manage, so he said. Adding to his poor sight, he had the effect of profound deafness. The advice given was, at best, poorly understood due to this loss of hearing. His refusal to allow either his son or daughter to attend other appointments frustrated us as we could not establish the veracity of what he was told. We also wanted to convey our concerns as his coping ability was diminishing.

Does the Dresscode Deceive?

Well-dressed people are judged and afforded positive latitude toward their well-being through their apparent responsible behaviour. He spoke well, was commanding, came over as in control, and needed help, but on his terms. That he died of cancer does not cause us concern, although not an end we would have wished for. The hospital’s policy and attitude were below the standard expected. Should the family sue the GP and the practice? Of course not. What value would that achieve? That said, I appreciated the openness between the GPs in the end. My view was that the father had tied their hands while observing his wishes, and they fell all too comfortable with his wishes.

I share this story as a passionate believer in the power of positive learning through not seeking fault but reviewing policies and attitudes. Not trying to blame anyone else serves more value. This was not a virus that had cruelly removed many loved ones from their families but a system called the NHS that rests on creaky, rusty hinges. Money will not fix the NHS until corrosive parts are replaced. My father was the architect of his own destiny. It could have been a better end, but he misled the medical profession, his family and himself for longer than would have been wise.

Other Cancer-related Articles at ConsultingFootPain

Topical articles:

Cancer and the foot

Five Conditions in feet caused by medication to treat cancers

Afni-Shah Hamilton is an experienced podiatrist and works with MacMillan Hospice. Many cancer treatments cause foot problems, and she wrote a series for this site to help patients. While foot cancer might be rare, the effects of treatment for cancer, including bowel cancer, certainly upset the foot.

Supplementary facts from podiatry

How can podiatry help with peripheral neuropathy?

How can podiatrists help with the toxic effect of medication on nails?

How can podiatrists help with Xerosis?

Thanks for reading ‘Caught Out with Cancer’ by David R Tollafield

Published by Busypencilcase Reflective Communications Est. 2015

Originally published 26 April 2021. Modified January 2025.

David is an author of patient guidebooks and writes about foot and other health concerns. His website and books can be found at davidtollafieldauthor.com

Recent Comments