The Butchering Art

Joseph Lister’s quest to transform the grisly world of Victorian Medicine

Lindsey Fitzharris ISBN 978-0-141-98338-7

Penguin Books 2018

First published in the USA by Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2017

Previously published in the UK by Allen Lane 2017 (AMAZON)

Changes in Victorian Surgery

This book review is brought to you by Ian Turbutt, a past senior member of the podiatry profession and former consultant podiatric surgeon. When Ian wrote and told me I should read this book, I had not realised how engaging it would be. Simply to remind us of the progress that we have made and how few infections arise from surgical intervention, given the complexity of our work today is a salutary reminder of the difference in training between the 19th to 21st centuries. I am indebted to him for providing this lovely review of a book I am sure anyone, perhaps with a strong stomach, might enjoy – if that is the correct phrase!

(Editor)

Histories and Horror of Medicine in Great Britain

Those of us with an interest in medical history will have seen many books describing in lurid detail the horrors of medicine and surgery in the early centuries. Grimly fascinating descriptions of pain and suffering can after all make interesting bedtime reading! This volume, written by the highly qualified and acclaimed Lindsey Fitzharris, has all the horror and bloody detail, but it also has so much more. Rigorously researched and referenced it chronicles the life and times mainly of Joseph Lister, but with necessary detail of other famous medical and surgical figures of the Victorian era and earlier.

In the 1840s surgery was an unrefined spectator sport for many not even in the medical field, hence of course the Operating Theatre. Speed was of the essence to reduce the awful suffering of patients, only later slightly tempered by the emergence of anaesthesia. The description of the procedure for excision of bladder stones is enough to bring tears to the eyes of any male! Comparatively rare numerically (in 1840 there were only 120 operations in Glasgow Royal Infirmary), surgery led to almost certain death from shock or subsequent infection, although the last reason was not truly recognised at that time. Purulence, ‘laudable pus’, was considered a good sign of the healing process. Medical training was evolving, beginning in the early 1800s, and teaching hospitals developed in London and Edinburgh. There were pioneers in surgical techniques, such as Robert Liston, but nobody could escape the facts that mortality rates, particularly in hospitals as opposed to procedures carried out at the patient’s domestic setting, had a three to five times higher morbidity rate. It was ironic that as the surgical procedures became more common, complex and refined, using the undoubted benefits of early anaesthesia, the morbidity rates also increased dramatically due to secondary sepsis. Who knew or attempted to understand why? Step forward Joseph Lister.

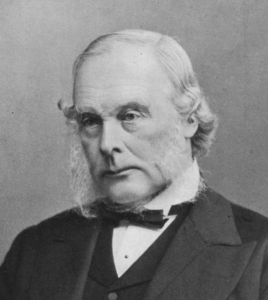

Joseph Lister 1827-1912

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/Joseph_Lister_1902.jpg

Joseph Lister was born in 1827 into a Quaker household where scientific interest was encouraged. His father was an expert in grinding precision optical lenses and Joseph grew to love time spent at the microscope. The book contains much fascinating detail about his early life and times and his later surgical training. His inquisitive, thoughtful, religious and sober character came to the fore throughout his career and perhaps set him apart from his contemporaries who enjoyed some of the excesses. He continued to study every possible organism and tissue under the microscope, even though it was considered a waste of time by many in England, as opposed to France where its usage was definitely increasing. The picture of slow medical evolution and training is brilliantly drawn in great and sometimes foul detail by the author. She brings in all the major players of the time and puts their efforts and interprofessional rivalry into context. The accounts of different attitudes and jealousies and perceived hierarchies that existed then between physicians and surgeons and their registrars, then known as ‘dressers’, evoke very persistent parallels in our modern day medical worlds. She demonstrates the serious risks that attached to being a surgical practitioner, death from infection being a distinct possibility, and the battles that patients had to get themselves treated in the 19thcentury are discussed. Arising from this quagmire, fighting his own demons leading to depression and mental collapse, emerged Joseph Lister….and his microscope.

Scottish Links

The book chronicles his early travels around Europe in 1848 followed by his appointment as a surgical dresser at University College Hospital commencing in 1850 and goes on to detail the prevailing very high death rates following surgery, amidst harrowing settings of carnage, sepsis, pus and stench. The internal arguments amongst the medical profession about causation raged with various theories and not a little disinterest from those who felt that any enquiry threatened their status. Lister was in some ways a daring young man, unafraid to put his skills to various tests and he in fact performed the first surgical procedure on the gut. All the while his enquiring mind returned to his microscopic work and physiology and he became interested in the work of Professor William Sharpey the physiologist. He later identified ‘materies morbi’, what we would now call bacteria, from scrapings of ulcers. He became accepted by many as a student with great ideas and was the recipient of distinctions and gold medals for his work. He moved to Scotland in 1853 and started to work as an assistant to Professor James Syme, a respected surgeon with a great ego and fiery temperament to match, at the Royal Infirmary Edinburgh. Lister was appointed house surgeon in 1854 then gained his Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of Scotland. He in fact fell in love with Syme’s daughter Agnes and married her.

Vivisection was not uncommon at the time, and the book details some upsetting studies done by Lister, particularly on frogs, and others on living breathing animals. It is definitely not a section for animal lovers. Fitzharris goes on to give riveting detail of Lister’s fairly amazing career and the battles he fought, both in the UK and abroad, to gain acceptance of his developing theories and methods of treating and preventing infection, as well as his own caring and compassionate personality and the faith that kept him going against many odds. As just one example he was held in enormous regard by his students at the University of Glasgow and Glasgow Royal Infirmary who supported him against intransigence from University authorities.

The book certainly gives very well researched information, including his developing relationship in the 1860s with Louis Pasteur, and the mutual respect they forged for each other, and his increasing realisation of the power of carbolic acid, and methods of its application, which revolutionised the risks of surgical intervention. Lister’s career was far too varied and complex to do it justice in this review. Fitzharris has made me realise more than ever how much this one man’s dogged yet quiet determination contributed to our current relatively safe existence, and it has made me incredibly grateful to him. I highly recommend that you read this biography….and wonder where we would be now if he had not existed.

Thanks for reading ‘Book Review Victorian Surgery’ by Ian Turbutt

Published by Busypencilcase Reflective Communications. Est. 2015

7th June 2021

Read more book reviews on ConsultingFootPain

The Remarkable Life of the Skin

Your Life in My Hands Book Review

Recent Comments